Some people misunderstood the intent of my last post. It was certainly condescending toward the "thieving" artist. But it was not in a sanctimonious-dean-accusing-a-student-of-plagiarism way, but in an experienced-thief-shaking-his-head-at-the-burglar-caught-by-leaving-tracks-in-the-snow kind of way.

Because let's face it: all artists are thieves, if you count being influenced by images or ideas that you didn't create as stealing*. So it's not "good artists borrow and great artists steal"; it's good artists clumsily pick-pocket, and great artists pull off the heist of the century. Great artists steal in ways that are either untraceable or in ways that are so masterful that nobody cares where it all came from.

So while I'm not one of the all-time great plunderers, for the sake of other bungling burglars out there I'd like to share the ways I've learned that you can steal and still "get away with it."

The Lookie Loo

Otherwise known as "using reference," this is the most fundamental grab-and-run operation. It consists of drawing or painting something that already exists, usually while the artist is looking directly at that thing. Sometimes the artist will set up a scene and then pilfer it verbatim, but other times he or she will pinch from smaller photos or art that describe the individual elements needed for the larger piece.

The Memory Game

Similar to the Lookie Loo, but in this case the artist steals imagery or ideas from things he or she has seen or been inspired by in the past. The beauty of this ploy is that the artist may perform the theft without even realizing it is happening. In order to avoid a surprise outcome with the Memory Game, artists may intentionally throw in a Combination Caper or layer in a Romance Scam to throw people off the scent.

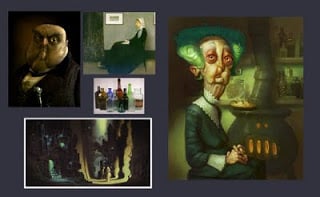

The Combination Caper

Here the artist lifts multiple ideas from different sources and fuses them together. The success of this caper relies on constructing an image from things the audience is already familiar with, so that they will subconsciously register each contribution as it influences their reaction to the piece.

The Parrot Ruse

Otherwise known as "quoting," in the Parrot Ruse the artist repeats a recognizable portion of another artists' work in order to establish context for his own message. By calling upon the viewers' familiarity with the work being quoted, the artist suckers them into thinking that his wholesale rip-off is acceptable because "it's ironic." The non-art equivalent to this would be stealing a Lambourghini in broad daylight while singing. Not only would people allow it: they would applaud afterward, assuming the theft was a clever part of a flash-mob.

The Romance Scam

Sure, the artist's character design isn't that original. But when everyone is looking at the way she's handled the lighting, or the emotional expression of the piece, most people don't even think about the design. The Romance scam works by misdirection---the artist hides her fraud in one area with fancy execution in another.

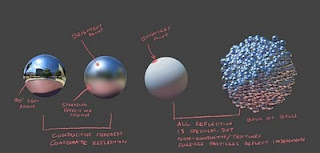

Salting the Line

This is one case in which an artist can get away with taking other art or photos directly, if it is done carefully. By layering in textures, patterns, or other effects from another source, the artist can quickly add polish and something interesting to his piece. This type of cheat only works when nobody recognizes the source being used, or if some combination of the sources creates an effect that masks the individuality of the plundered pieces.

The Chop Shop

Think of it as a collage of crime. This one is commonly used by digital matte painters, who need to create a sense of realism, but do not have the time or inclination to paint in every leaf on every tree. In order to pull off a Chop Shop successfully, the artist has to know something about composition and how to get things to fit together. The artist's primary goal in a Chop Shop job is assembling his ill-gotten goods in an appealing way.

Scams that Don't Work (Anymore)

The Pablo Pipoppycock

Don't have any original ideas? Just vandalize one of your lifted ideas with some crazy effect and call it "modern." This lowbrow version of the Romance Scam appeals to people's fear of being considered less intelligent than others. Just be aware that, even if your lengthy essay explaining the piece impresses your art school buddies, you can't expect to win any points in accomplished art crook circles. It's a small-time scam and we've all tried it at least once, but the real satisfaction is found in bigger heists.

The Snake Oil Swindle

Selling a product made by someone else as your own? We all know that direct copies and studies have value to you personally, but don't try to profit from them unless your big dreams as an artist include being blackballed by at least a corner of the industry.

The Flemish Prisoner

This is when the artist decides that, since nothing is original anyway, he or she will just paint the same boring things as everyone else and not ever even attempt to have an original thought. Mastering a technique, but not developing the ideas beyond stage one, is just a waste of potential.

*Disclaimer: I'm not condoning actual art theft, of the literal or figurative variety. In fact, I don't believe artists are thieves any more than I believe that artists are accountants. I DO believe in relaxing a little and appreciating the fact that all artists are standing on the shoulders of giants. Please don't begrudge another artist if they are standing on your shoulders; because you've enjoyed the same courtesy from other artists around the world and throughout history.

Because let's face it: all artists are thieves, if you count being influenced by images or ideas that you didn't create as stealing*. So it's not "good artists borrow and great artists steal"; it's good artists clumsily pick-pocket, and great artists pull off the heist of the century. Great artists steal in ways that are either untraceable or in ways that are so masterful that nobody cares where it all came from.

So while I'm not one of the all-time great plunderers, for the sake of other bungling burglars out there I'd like to share the ways I've learned that you can steal and still "get away with it."

The Lookie Loo

Otherwise known as "using reference," this is the most fundamental grab-and-run operation. It consists of drawing or painting something that already exists, usually while the artist is looking directly at that thing. Sometimes the artist will set up a scene and then pilfer it verbatim, but other times he or she will pinch from smaller photos or art that describe the individual elements needed for the larger piece.

The Memory Game

Similar to the Lookie Loo, but in this case the artist steals imagery or ideas from things he or she has seen or been inspired by in the past. The beauty of this ploy is that the artist may perform the theft without even realizing it is happening. In order to avoid a surprise outcome with the Memory Game, artists may intentionally throw in a Combination Caper or layer in a Romance Scam to throw people off the scent.

The Combination Caper

Here the artist lifts multiple ideas from different sources and fuses them together. The success of this caper relies on constructing an image from things the audience is already familiar with, so that they will subconsciously register each contribution as it influences their reaction to the piece.

The Parrot Ruse

Otherwise known as "quoting," in the Parrot Ruse the artist repeats a recognizable portion of another artists' work in order to establish context for his own message. By calling upon the viewers' familiarity with the work being quoted, the artist suckers them into thinking that his wholesale rip-off is acceptable because "it's ironic." The non-art equivalent to this would be stealing a Lambourghini in broad daylight while singing. Not only would people allow it: they would applaud afterward, assuming the theft was a clever part of a flash-mob.

The Romance Scam

Sure, the artist's character design isn't that original. But when everyone is looking at the way she's handled the lighting, or the emotional expression of the piece, most people don't even think about the design. The Romance scam works by misdirection---the artist hides her fraud in one area with fancy execution in another.

|

| I'm pretty sure I didn't paint all these textures from scratch |

This is one case in which an artist can get away with taking other art or photos directly, if it is done carefully. By layering in textures, patterns, or other effects from another source, the artist can quickly add polish and something interesting to his piece. This type of cheat only works when nobody recognizes the source being used, or if some combination of the sources creates an effect that masks the individuality of the plundered pieces.

The Chop Shop

Think of it as a collage of crime. This one is commonly used by digital matte painters, who need to create a sense of realism, but do not have the time or inclination to paint in every leaf on every tree. In order to pull off a Chop Shop successfully, the artist has to know something about composition and how to get things to fit together. The artist's primary goal in a Chop Shop job is assembling his ill-gotten goods in an appealing way.

Scams that Don't Work (Anymore)

The Pablo Pipoppycock

Don't have any original ideas? Just vandalize one of your lifted ideas with some crazy effect and call it "modern." This lowbrow version of the Romance Scam appeals to people's fear of being considered less intelligent than others. Just be aware that, even if your lengthy essay explaining the piece impresses your art school buddies, you can't expect to win any points in accomplished art crook circles. It's a small-time scam and we've all tried it at least once, but the real satisfaction is found in bigger heists.

The Snake Oil Swindle

Selling a product made by someone else as your own? We all know that direct copies and studies have value to you personally, but don't try to profit from them unless your big dreams as an artist include being blackballed by at least a corner of the industry.

The Flemish Prisoner

This is when the artist decides that, since nothing is original anyway, he or she will just paint the same boring things as everyone else and not ever even attempt to have an original thought. Mastering a technique, but not developing the ideas beyond stage one, is just a waste of potential.

*Disclaimer: I'm not condoning actual art theft, of the literal or figurative variety. In fact, I don't believe artists are thieves any more than I believe that artists are accountants. I DO believe in relaxing a little and appreciating the fact that all artists are standing on the shoulders of giants. Please don't begrudge another artist if they are standing on your shoulders; because you've enjoyed the same courtesy from other artists around the world and throughout history.